C36M

Paulatuk, NT, CAN

The USArray component of the NSF-funded EarthScope project ended its observational period in September 2021 and all remaining close-out tasks concluded in March 2022. Hundreds of seismic stations were transferred to other operators and continue to collect scientific observations. This USArray.org website is now in an archival state and will no longer be updated. To learn more about this project and the science it continues to enable, please view publications here: http://usarray.org/researchers/pubs and citations of the Transportable Array network DOI 10.7914/SN/TA.

To further advance geophysics support for the geophysics community, UNAVCO and IRIS are merging. The merged organization will be called EarthScope Consortium. As our science becomes more convergent, there is benefit to examining how we can support research and education as a single organization to conduct and advance cutting-edge geophysics. See our Joining Forces website for more information. The site earthscope.org will soon host the new EarthScope Consortium website.

By Maia ten Brink

Spiral Jetty, Robert Smithson’s earthwork of mud and basalt, uncurls like a giant chameleon’s tongue taking a drink from the Great Salt Lake.

Spiral Jetty

It’s an 80 km drive west of Brigham City, Utah, and once you get there, the sculpture might not even be visible, depending on the seasonal rains. Graylan Vincent visited Spiral Jetty one August evening in 2006 after finding a site for an earthquake sensor on a nearby ranch. The winding drive up to the earthwork did not seem so ludicrous compared to some of the journeys he had made while hunting for remote, undisturbed locations to place the hundreds of other seismometers that constitute the EarthScope Transportable Array. In fact, Vincent kind of liked how Spiral Jetty was in the middle of nowhere.

He arrived just after sunset and waded out in the warm air and saltwater. Barefoot in the twilight, Vincent filled with a sense of peace. This was why he had taken the reconnaissance job with the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS). This was why he drove around the United States asking strangers to host a seismometer on their property and why he spent ten days out of every two weeks on the road, either in the seat of his pickup or in identically decorated hotel rooms. “Holy smokes,” he thought, “I get paid to travel the country.”

You can count on Graylan Vincent to be unabashedly interested in things. He has just spent eight years talking to strangers for his job, finding points of connection with them, and it’s clear that he relishes conversation. He has explained the EarthScope Transportable Array, IRIS’ nationwide seismology experiment, to hundreds of landowners all over the country. He estimates that he has repeated his spiel—“Hi, I’m Graylan and I’m out here looking for someplace to put an earthquake sensor for a research project”—at least 800 times during the last eight years. Vincent is thirty-three but looks like a lanky college student with cargo shorts and a windbreaker tied around his waist, bouncing on the balls of his feet. He swears all the time, with excited abandon. After eight years of travel, he says, somehow, “I still have a bit of wanderlust.”

America boasts more miles of road than any other country in the world—nearly 6.5 million kilometers, according to the Department of Transportation.1 It’s an infrastructure that rivals ancient Rome’s. In the last eight years, Vincent drove over 300,000 kilometers on those roads. That’s about one light-second, or 80% of the distance to the moon. If he drove continuously at highway speeds (about 96 kilometers per hour), that amounts to driving 24 hours a day for 463 days straight.

Road atlases from travels

around the United States.

Vincent listened to music, podcasts, and NPR as he drove. He recalls “a lot of talking to myself.” He passed the Oscar Meyer Weinermobile twice. His travels took him down the furthest capillaries of dirt roads and deadest ends of the nowhere-est towns in America.

“It’s a unique lifestyle,” admits Vincent. “You meet a lot of ‘road warriors,’ as the term is.” He estimates that by now he’s spent a total of five or six years of his life in hotels or restaurants. “I can throw a dart at a map of the country and I can tell you where to eat where it lands,” he laughs. “I can identify a hotel by its hairdryer.” After his first day on the job, he did laps in the hotel pool, intending to exercise away the long hours spent at the wheel. “Yeah… that lasted one day,” he chuckles guiltily.

Vincent visited 47 states, three provinces, and one territory in total.

Graylan Vincent staking out a seismic station.

Northern Minnesota, Utah, Nevada, the Guadalupe Mountains in West Texas, and central and western Montana make up his top-five list. “There are beautiful places all around the country that I didn’t know existed,” he says. “Prior to this job, I had driven across the country once, but I felt like a sailboat in the ocean. Everything around me was foreign. Now the whole country, it’s not this big unknown thing.”

The challenge of reconnaissance work was getting strangers to grant Vincent a favor in the name of science. As soon as he pulled up to a property and stepped out of his truck, he needed to put the landowners at ease. The first two sentences out of his mouth could secure a site or sabotage it. His technique: “Keep it short, sweet, blindingly honest—enough to catch them off guard. Be straightforward and quick before they have time to develop a defensive tactic.” He has practiced his speaking voice—polite, direct, and sincere, with an audible grin.

Don Lippert trained Vincent during his first month. At Vincent’s very first site, he and Lippert drove up a narrow dusty road outside Winslow, Arizona. “There’s a gentleman sittin’ in the chair just outside his garage, just sittin’ there, kickin’ back, but he had a gun on in his holster,” says Lippert. “The guy turned out to be very nice… He could see that Graylan was just out of school so he gave him a bad time. He said, ‘Oh, c’mon, you gotta fire a gun.’ He had a big .44 Magnum or something, a pistol. Graylan shot that a couple of times. It was sorta fun. An hour later, we had a site and we were gone.”

“It was a honkin’ huge dirty hairy gun,” Vincent recalls with awe.

Vincent primarily interacted with farmers and ranchers whose properties had plenty of space to host a seismometer. “A lot of my job was approaching people working on their tractor or in their shop,” says Vincent. “I’d wave at them to get their attention, and they’d wonder, ‘Who is this yahoo?’” He thinks that someone from agriculture school would have been better suited to his job because they could have bonded with landowners over tractors; he holds degrees from the University of Washington in the more esoteric fields of geology and aerospace engineering.

Traveling made him confront his own stereotypes about rural America.

Stop sign for horses.

To save time, Vincent often tried to figure out whether a landowner would want to participate in the EarthScope experiment based on “their land, what kind of house, vehicles, tractors, whether [he] saw a dog, whether [he] saw college flags.”

He admits that the system never worked. “I met friendly people everywhere, regardless of how they lived and what they drove. You’ve got to meet them; you can’t make assumptions.”

In southwestern Arizona, Vincent came across one dusty retiree whose ranch looked, to his eyes, like a machinery graveyard overrun with dogs. “I thought of him as an old rancher,” Vincent says, “but I learned he was an engineer and he had designed the batteries for the International Space Station.” The ranch was his hobby farm. He enjoyed fixing broken machinery and his wife ran a dog rescue. “That just took my brain, flipped it upside-down, and punched it through the field goal,” says Vincent.

After completing his tour of the nation, Vincent has concluded that “anywhere you go, people are pretty much the same. People are willing to help you out if you give them the chance and get to know them one-on-one… People have some really different accents, different politics, different crops or farming techniques, but that’s all. Maybe that wouldn’t have been the case fifty or seventy years ago, before Internet, before cable.”

The Transportable Array stations moved across the country in a stripe from west to east, and Vincent tried to work from north to south in order to stay ahead of the snow. His goal was to find seismometer sites spaced every 70 km, but he could go about it nearly any way he chose.

There is, in fact, a famous quandary in computational mathematics that deals with that very question. The traveling salesman problem, or the TSP, involves calculating the shortest-distance round-trip route between n number of cities. Unfortunately, when you add more cities to the route, the number of possible routes increases exponentially. Just 15 cities yields tens of billions of permutations.2

Vincent’s route between seismometer sites was definitely not the most efficient solution for his personal traveling salesman problem.

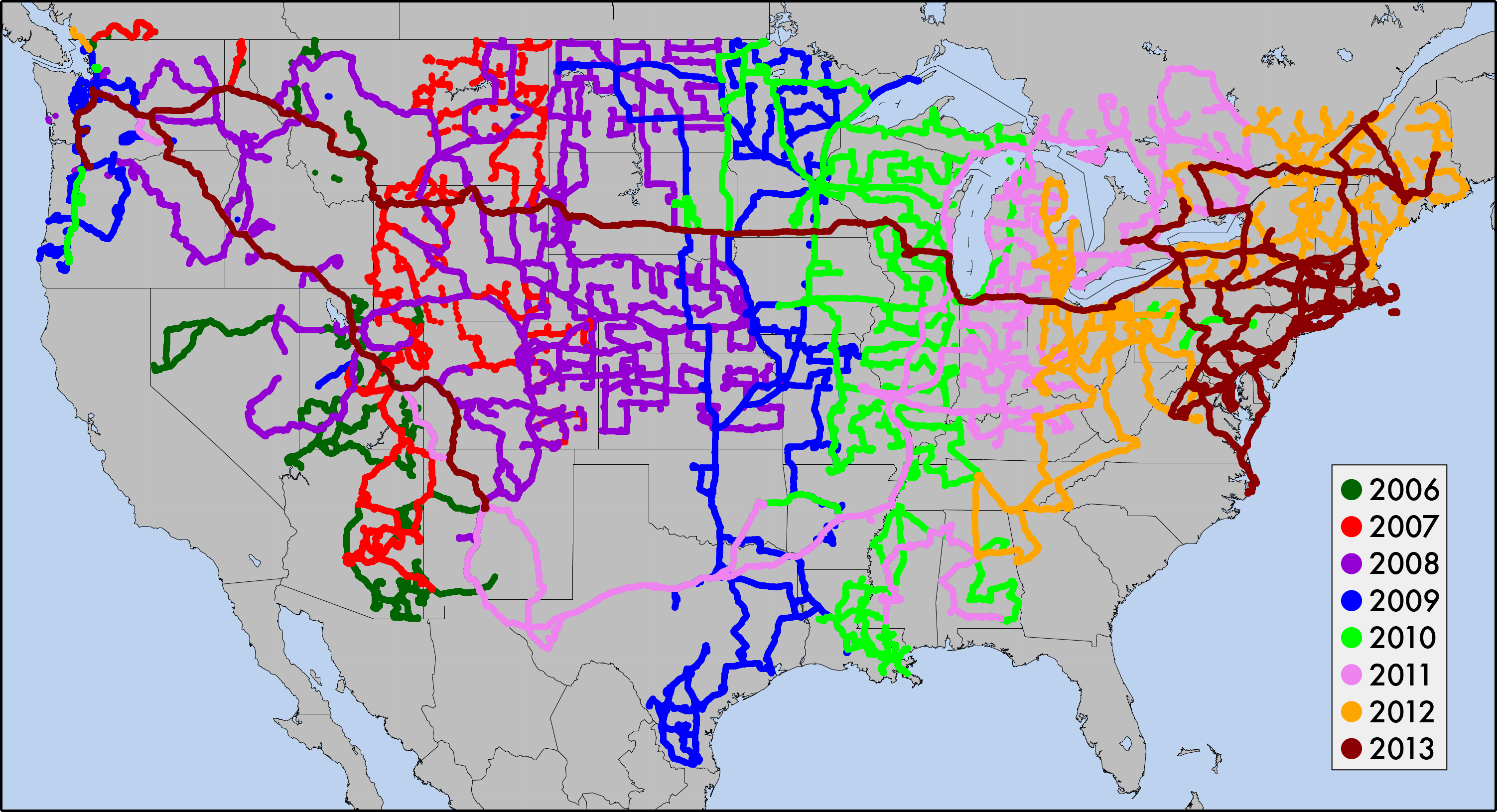

Graylan's GPS trajectories mapped over time.

Note that a few of the early tracks are missing.

Credit: Graylan Vincent and Andy Frassetto.

He liked to stop and get to know places. His trajectories, tracked on his GPS (nicknamed Sheila because he programmed her to have an Australian accent—“more friendly to deal with”), look like a spider’s embroidery.

“I took little detours here and there, whatever chance I got,” says Vincent. “The Black Hills of South Dakota. The Wind Cave, the Jewel Cave… Anytime there was anything that would be interesting, I’d pull over and stop.” Along Kansas State Highway 47, a crowd of welded wire dinosaurs munches the grass. Maine has a scaled model of the solar system.

Vincent made it his particular mission to see as many art museums and pieces of land art as he could. Spiral Jetty is one of more than a dozen monumental land artworks around the United States that blur the line between sculpture and geology. “There's something about the scale, boldness, and desolate locations of these works that I love. Plus the adventure of getting to them,” Vincent explains.

Vincent got lost in someone’s cattle pasture outside Flagstaff, Arizona, while trying to get to Roden Crater, an extinct cinder cone volcano that artist James Turrell landscaped into what Vincent calls “a giant art piece/temple/observatory/…thing.” His truck got stuck on the way to Michael Heizer’s earthwork Double Negative. He noticed a Jeep abandoned on the road up ahead, but didn’t see the mud until his own wheels had sunk in it. The Jeep’s owner returned with help a few minutes later, and they used the winch on the back of Vincent’s truck to pull both vehicles out. When he finally arrived, it was too dark to see much—“basically a pit dug in the ground across a canyon. But,” he says, “it’s more of the journey of getting out to these places.”

Roden Crater.

In northern Minnesota, Vincent heard about the Soudan Mine, an old iron mine that now houses an underground particle physics laboratory. He rode an old mining elevator 0.8 km down to the Soudan Underground Laboratory, a research facility run by the University of Minnesota that studies neutrinos and dark matter. Picture two caverns, each about six times the volume of an Olympic swimming pool, carved out of 2.7-billion-year-old green metamorphic rock that formed when lava hardened underwater. Beams of neutrinos are shot from the Fermi National Accelerator near Chicago, located about 700 km away, at 8-meter-wide octagonal detector plates that weigh as much as navy destroyers. “I stuck around an extra day just to go on that tour,” says Vincent. “It was really cool.”

He loved visiting national parks. “In southwestern Utah, there’s a Transportable Array site in the middle of nowhere, site S018A.” It was hours away from any hotels, so Vincent stopped at the nearby Natural Bridges National Monument to camp overnight. He pitched his tent and curled up in his sleeping bag. As his eyes adjusted, he noticed that his tent was illuminated.

“I look up and realize there’s no moon, and then I look a little bit harder and realize, it’s the Milky Way that’s lighting up my tent! I just sit there with my mouth open. It’s so bright! Not light I’d be able to read by, but I could find my way around. Not only could you see the Milky Way, you see the galactic dust clouds that are blocking the Milky Way.”

Vincent retrieved his binoculars from his truck and fell asleep with his head sticking out of the tent, gazing up at the spangled sky. He later realized that Natural Bridges National Monument had been declared the first international dark sky park—a place where no artificial light obscures the nighttime vista. According to the National Park Service, some 15,000 stars are visible from Natural Bridges National Monument, while only 500 stars can be seen in populated areas. “As far as eye-opening experiences,” Vincent says, “that’s one I’ll remember.”

Eight years of mowing rows across the country took its toll on Vincent. He would fly out of Seattle on a Monday and fly home the following Wednesday. He couldn’t commit to any regular schedule, maintain a gym membership, or stay current with his Volunteer Search and Rescue certification. He found it difficult to adjust to the city after spending weeks in near-total isolation.

“Day to day, I had so little interaction,” says Vincent. “It wore me down. I got burned out, tired of traveling. All the long airline flights. I’m kind of tall. I got tired of not having a life. I really missed getting to take classes and being in a learning environment.”

Don Lippert, who trained and supervised Vincent, explains, “At the end, this wasn’t him. He was on ten days, off four, so he was gettin’ antsy.”

In August of 2013, Vincent finally threw in the towel after he finished locating the very last Transportable Array site on the East Coast. The project’s scientific rewards as the world’s largest seismic data set motivated him to stick around until all the reconnaissance was “tucked into bed, squared away.”

“Because of USArray and EarthScope, we expect a whole lot more students going into geophysics and seismology,” says Vincent. “Before USArray, you’d have to apply for a grant, borrow equipment, deploy seismometers, recover the equipment, and try to work on results. That’s going to take you years. Now you can download a USArray data set in about a second.” On top of that, Vincent says, the data are accurate and high quality. “That’s directly because of the reconnaissance. I’m really proud.”

Now Vincent is in what he jokingly calls “early retirement” in Seattle. He takes woodworking classes at community college, bikes around, and revels in the knowledge that he doesn’t have to set foot in Sea-Tac Airport.

“I don’t have these multi-hour drives anymore. It’s just these five-minute hops. Not even long enough to listen to a podcast,” he grins.

He relishes spending time with people, especially now that he can hang around for longer than a few days. When new acquaintances tell him, “I’m from a teeny little town in someplace-or-other,” Vincent will respond, “Oh, yeah, I ate barbecue there.” He likes eliciting a shocked “What were you doing out there?”

Vincent has a photograph he took that the warm evening at Spiral Jetty as his computer desktop background. It’s a visual reminder of a journey that took him around the United States—and around and around and around and around again.

_____________

1Twenty percent of the world’s passenger vehicles and 40% of the world’s buses and trucks are driving on American roads at any given time. Each year, Americans rack up about 3.5 trillion vehicle-kilometers of travel.

2 Solving a TSP means finding the shortest route and making sure that none of the other possible routes are shorter—a tall order when you have to test a number of possibilities so huge that we don’t even have a name to describe it.

No one has yet discovered a single algorithm that can efficiently solve any TSP with any number of cities. The most recent breakthrough occurred in 2011, when computer scientists solved an 85,900-city TSP with an approximate route that was 49.99999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999996% longer (as opposed to the previous record of 50%) than the most optimal route.

With each TSP challenge involving more and more cities, mathematicians and computer scientists continue to push the limits of computational theory. The TSP’s applications include DNA sequencing, computer wiring, neural networks, microchip manufacturing, scheduling, and logistics. Robert Bosch even created a TSP Mona Lisa that forms a continuous-line drawing between 100,000 points.

Biologists have also taken a crack at the TSP. It turns out that slime molds and ant colonies, not just computers, can solve traveling salesmen problems. A single-celled slime mold, Physalum polycepharum, spreads over unfamiliar areas, and then prunes back its growth until it has established the shortest-distance pathways that connect it to food sources. Ants sniff out pheromones from other ants to find the shortest distance to delicious crumbs.

For more wacky roadside attractions, see http://www.roadsideamerica.com/