K04D

Chiloquin, OR, USA

The USArray component of the NSF-funded EarthScope project ended its observational period in September 2021 and all remaining close-out tasks concluded in March 2022. Hundreds of seismic stations were transferred to other operators and continue to collect scientific observations. This USArray.org website is now in an archival state and will no longer be updated. To learn more about this project and the science it continues to enable, please view publications here: http://usarray.org/researchers/pubs and citations of the Transportable Array network DOI 10.7914/SN/TA.

To further advance geophysics support for the geophysics community, UNAVCO and IRIS are merging. The merged organization will be called EarthScope Consortium. As our science becomes more convergent, there is benefit to examining how we can support research and education as a single organization to conduct and advance cutting-edge geophysics. See our Joining Forces website for more information. The site earthscope.org will soon host the new EarthScope Consortium website.

By Maia ten Brink

Ben Johnson was kneeling in a stranger’s backyard, setting a stake in the ground to mark the spot for a seismometer. He and his partner Jamie Ryan, both geology undergraduates at Michigan State University, had spent a day and a half on the outskirts of Lansing, going door-to-door, looking for property far from all human activity. They were siting locations for 25 seismometer stations in a grid across eastern Michigan. Their region was just one patch in a quilt of seismometers called USArray that would cover the United States with over a thousand seismic stations spaced every 70 kilometers.

It was Johnson’s first site; he was a little nervous about getting it right. As he bent down to hammer the stake, he backed his rear end against the electric fence around the landowner’s donkey pen. ZAP! He stood up like a shot, not quite sure what had happened. He wasn’t hurt, but felt a little shaken. For the rest of the day, he said, “I was just not the same.”

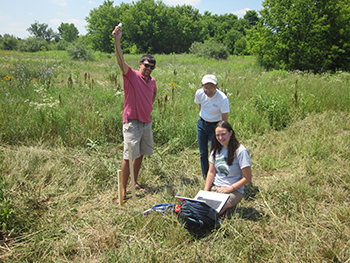

Ben, Jamie, and Professor Fujita inspect a potential site.

That summer of 2011, teams of geology students like Johnson and Ryan racked up over 8000 kilometers driving around the Midwest, knocking on doors at ranches, farms, and rural properties. Each group of two or three students had to find 25 landowners willing to let scientists dig a refrigerator-sized hole on their property and leave a seismometer buried in the ground for two years. The students had two and a half months, some maps, a laptop, a car, and a cell modem. Go.

Finding a suitable site had been harder than Johnson expected. He and Ryan had scoped out possible locations using Google Earth’s satellite images, but some landowners turned them away or weren’t home, and some sites turned out to be too “noisy” to host a seismometer. The seismometers used in the USArray are sensitive enough to register small earthquakes on the other side of the world, trains passing eight to thirteen kilometers away, and even trees shaking the earth as they bend in the wind.

After an unsuccessful morning, Johnson stopped at a house with a porch cluttered with children’s toys. Johnson had to work up the courage to approach; he hadn’t gone door-to-door since selling popcorn in the Boy Scouts. He picked his way around the plastic cars on the porch and rang the doorbell at what appeared to be the front door. No one answered. As he got back in the car, a man came out from behind the house and stared at him. Johnson hissed to his partner, “What do I do? Should I go talk to him? Should we just get out of here? He doesn’t look very happy to see us.” Ryan pushed Johnson to go introduce himself.

“Hey, my name is Ben and this is Jamie. We’re geologists from Michigan State,” said Johnson, holding out his hand to the man. He mentioned Michigan State because he wanted landowners to feel connected to a local institution. “We’re working on a large earthquake survey and we’re installing sensors to monitor earthquakes. We’re looking for somewhere out in the middle of nowhere, where we’re not bothering anybody, where we can place an instrument for two years. You seem to have some property out there. We’re potentially looking at your property for a site. Is this something you would be interested in?”

The landowner, Rick, was a mechanic working nights. He had been at the back of the house and missed the doorbell. He took care of his child during the day, played violin in his spare time, and had a niece at Michigan State. He smiled and immediately offered to show them his land, which he used to grow hay for his donkey and horse. Johnson and Ryan pulled out their instruments to assess the site — checking the soil, measuring the distance to the house and trees, looking for signs of animals, finding an electricity source, assessing shade to make sure that the station’s solar panels would function, and using their cell modem and laptop to measure the strength of the cellular signal to ensure that real-time data could be sent from the seismometer to be aggregated and analyzed in San Diego. That was when Johnson bumped his rump into the electric fence.

That site was a shock to Johnson in more ways than one. “It was so eye-opening to me. I had this pre-conceived notion that people in the country wanted to be left alone and didn’t want to be bothered, especially by some government-funded project, but people were really understanding,” he said.

With practice, Johnson streamlined his pitch and the team’s success rate improved. He focused on making personal connections and told them they would be part of a massive national science experiment. Johnson and Ryan also developed a finely tuned intuition about which houses to approach — almost a superstition. They looked for fields growing hay or lying fallow, properties larger than 40 acres, short driveways, and friendly animals. “I had to have a certain feeling about a house. There were a lot of houses we drove by and it was strictly based on a feeling,” Johnson said. The closer to the metro-Detroit area, the more hesitant and protective the landowners were. In the north, Johnson found landowners were more laid-back and had more available land. If people were home, Johnson estimated, 75% of the time they said yes.

“When I went through the workshop, I thought, ‘There’s no way this is as successful as they say it is.’” But Johnson and Ryan met schoolteachers, engineers, truck drivers, farmers, and war veterans who were willing and excited to host a seismic station. The team spent half a day talking to a hippie from the University of Michigan. They met up with a guy toting a large rock (“I figured, you’re geologists; you’d find me because I had this big rock with me”) in a tavern called Fisherman’s Happy Hour. They put a site near a cherry orchard at the northwest tip of the Michigan mitten, overlooking both Lake Michigan and the Grand Traverse Bay. They walked up to a house where a man was slaughtering chickens, his pants covered in guts. His dog ran up to them, chewing on a chicken foot. Ryan, who was a vegetarian and an animal-lover, looked a little queasy.

“We had a lady in one of the towns, she served us ice cream. I thought she was going to invite us to the family reunion that she had to go to,” Johnson said. “Some people were like, ‘Yeah, whatever. I’m going to the store. Help yourself to the fridge. Do whatever you want to do.’ And then there were some people who were really interested, and they wanted to talk to you.”

Near Saginaw, they spoke to a mother with two daughters. When Johnson explained that the girls could jump up and down beside the seismometer and then look online to see the vibration appear as a wiggle on the live seismogram, the older daughter immediately ran to look up the IRIS website. “I was telling her all about seismic waves. To me, that was a really special moment,” Johnson said. “People had been interested, but to see somebody young like that getting excited about earthquakes was really great.”

For two months, Johnson and Ryan meandered around the state, spending hours at the wheel of their rented Dodge Caliber, listening to Rush Limbaugh or the same 40 pop songs repeated on every radio station. Most nights, they stopped to sleep in EconoLodges. Johnson is a native of Grand Rapids, Michigan, but he visited parts of the state he’d never heard of. Ryan always got excited about roadside attractions. “I think her positive attitude toward being on the road really helped my positive attitude,” Johnson said. They visited a covered bridge in Frankenbuth, a year-round Christmas town known as “Michigan’s Little Bavaria” with a Cheese Haus and gift shops selling leiderhosen. They went swimming in both Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. They climbed a drumlin hill on the Leelanau Peninsula, formed when glaciers retreated back over the Canadian border around 10,000 years ago.

“When I look back on it, I miss the job. It was sort of gratifying because you had this big map in your office, and you had so many sites that you had to get. It was clear. When you completed the goal, you accomplished something,” Johnson said. “It’s completely different from science. There’s nothing tangible about completing something in science. It was such a nice relief for me.” (He laughed a little ruefully as he said this; he’s now a graduate student studying structural geology at West Virginia University.)

Johnson and Ryan would submit reconnaissance reports for their finished sites online and check the progress of other teams they had met back in May at IRIS’ student siting workshop. “It was a big race to be the first ones finished. I think that’s also what bonded Jamie and I. We wanted to do a good job because we had this competitive feeling that, if we’re not out getting a site, Indiana is going to get ahead of us by two sites.”

Working so closely with Ryan prepared Johnson for other team efforts. He said, “We spent all that time trying to figure out where our strengths and weaknesses were in that dynamic. Jamie was always really quiet, but she was super organized. She did a lot of the pre-assessment of sites, looking on Google Earth, finding potential sites. Me, I was the outgoing one. I would initiate the conversations, but Jamie was always there to correct me when I had something wrong, keeping us on task. She filled in all the holes.” She was also good with animals. “When dogs came up and were barking aggressively—I called her the Dog Whisperer—she could always calm the animal down, get the animal to warm up to us,” Johnson remembers.

Even though he started the summer dreading interactions with strangers, Johnson learned how to talk to just about anybody. “It was as much a random sample of the public in the state of Michigan as you could possibly get. There was just a wide range of people with different backgrounds. Being able to convey the basic idea behind a really large, complicated national project was definitely a skill I will always carry with me.”